Using Design Thinking to Enhance Medical Education Curriculum Development

Design thinking combines mindset, method, and process to confront difficult challenges. The goal of design thinking is to surface creative solutions that resonate with the people they are designed for. It originated in the 1960s with its use in product design and has since been popularized in other fields, such as business, technology, law, primary and secondary education, and sciences.

Recently, design thinking has become more popular for use in medical education. In this space, design thinking is relevant for curriculum development. Through design thinking, the learner's needs and preferences are revealed in a fresh light, and the process can then lead to the discovery of unseen possibilities for designing educational activities that inspire learners.

What is Design Thinking?

Design thinking is a powerful process that requires a growth mindset to develop inventive solutions. An inquisitive mindset and desire to seek new learning are necessary for design thinking. Design thinking also requires being empathic to the needs and context of other individuals, valuing differing opinions, engaging in collaborative working, accepting uncertainty and the associated risk, and having the desire to make a difference. This mindset, along with the iterative design thinking process, can foster innovation where services are delivered, and complex issues exist.

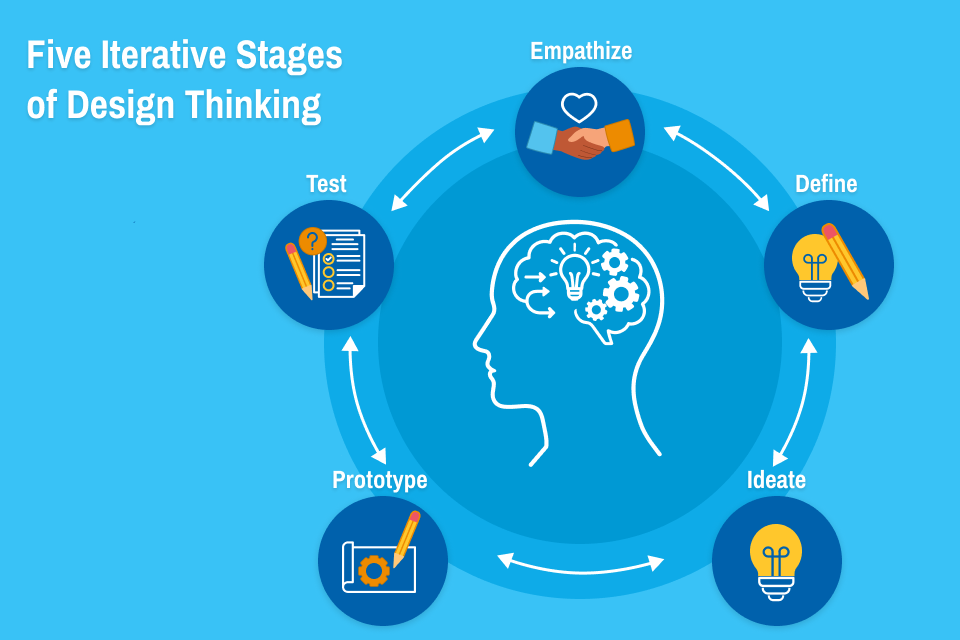

Design thinking involves two basic features. The first is thinking broadly to collect a variety of creative ideas about a problem. The second is putting the new ideas into action. The most common approach in medical education has five iterative stages:

- Empathize: Design thinking is deeply grounded in fully understanding the real needs of the end user, in this case the learner. To discover this, interviews with learners and observation are two highly valuable methods. Observing helps to see areas where learner needs are unmet, yet where the learners themselves are unaware and therefore unable to articulate. In this way, the invisible, not just the obvious problem is seen. The empathizing stage helps differentiate design thinking from other types of brainstorming.

- Define: Interpretations can transform the observations from the prior step into meaningful insights that inform appropriate questions to consider. These understandings of the learner's experience from different perspectives help pinpoint the right questions to ask, providing a specific focus to create from. It is important to formulate the right inquiry as a foundation so that the illuminated solutions speak to the real needs of the learners.

- Ideate: Assemble a team of people with a range of viewpoints from across a variety of specialties. Use the prompt, “how might we?” to assume there is a solution and defer judgment. Encourage ideas from apparent to absurd to discover connections and generate unexpected suggestions. Then, narrow these down by consensus to a smaller number of ideas that are carried onto the next phase.

- Prototype: During this experimental stage, prototypes are created to understand how learners respond to ideas and how ideas can be refined to optimally align with learner needs. Quick, inexpensive prototypes can be basic, as simple as a drawing, or refined, such as real-world inspired simulations. Run several prototypes to test various assumptions. The protypes can then be refined or discarded based on user feedback.

- Test: This involves the development of the chosen prototype and the changes that occur after implementation. Design thinking is a cyclical and iterative process. It is common to cycle back through the earlier stages multiple times prior to finding the best solution.

Design Thinking in Action

Design thinking case studies in medical education curricula range from small to large scale. Design thinking has been used to create and reform medical school curricula at several large institutions. Within complex medical education course design, such as in classes covering topics such as organ transplantation and interprofessional learning about aging and disability, design thinking has been successfully employed.

One clear example involves design thinking being used to redesign a radiology resident ultrasound experience to make it more engaging. The initiative was prompted by responses to a survey. In the design thinking process, residents identified “pain points” and subsequently generated rapid-fire solution ideas, writing each on a Post-it note. The group followed this step by voting on the top “big ideas.” New resources were developed using a combination of ideas found helpful in prototyping. This included a one-week boot camp with activities, relevant articles, and practice cases. The rotation was also restructured to include procedure time, and resident conferences were updated to be more relevant and stimulating. These changes have now been in place for several years with slight modifications in the timing of simulation experiences based on ongoing resident feedback and conversations.

Design Thinking Benefits

Design thinking is a compatible strategy to implement in medical education. It is both human-centered and focused on the end-user. However, design thinking builds upon the existing traditional approach to curricular design by significantly increasing the incorporation of qualitative and divergent thinking. Another advantage of using design thinking compared to traditional curriculum development is that design thinking’s rapid reiterative nature grants a “fail fast” format, so time is not spent on curriculare implementation that in the end receives poor user review. The design thinking system, additionally, simplifies tough situations, reducing frustration. Finally, design thinking allows voice from all participants to contribute given the lack of hierarchical structure, maximizing diverse input leading to potentially superior solutions.

Design Thinking Considerations

While design thinking can yield valuable results which may be unachievable through other means, it is important to remain cognizant of the resources required. From end to end, it can be time-consuming. Additionally, with the inclusion of multiple people in the process, it is critical that all remain open and actively involved. However, if this is a drawback, leveraging only a few of the tools or components of the process can still lead to notable results. At times, changing the status quo arrangement of exercises for learners using design thinking can broach unfounded territory and make a difference in impactful ways.

Ginger Adkins is the CEDAR Program Coordinator. She has a Master of Education in Adult

and Higher Education from the University of Missouri in St. Louis. Adkins has more

than seven years of experience in medical and health professions education. She has

expertise in experiential learning, accreditation, and OSCE coordination. Ginger can

be followed on LinkedIn or contacted via email.

Ginger Adkins is the CEDAR Program Coordinator. She has a Master of Education in Adult

and Higher Education from the University of Missouri in St. Louis. Adkins has more

than seven years of experience in medical and health professions education. She has

expertise in experiential learning, accreditation, and OSCE coordination. Ginger can

be followed on LinkedIn or contacted via email.